To make use of an RSS feed, you need some "feed reader" (or "aggregator") software. Most modern web browsers have feed readers built in.

The RSS feeds for Northside Creative Photography are listed below...

Northside Creative Photography upcoming events:

https://www.ncp.org.au/dbaction.php?action=rss&dbase=events

Northside Creative Photography news:

https://www.ncp.org.au/dbaction.php?action=rss&dbase=uploads

In Memorium

We remember Arch Raymond and Mary Raymond here.

To read in memorium for Richard Warburton click here.

To read in memorium for Peter Sambell click here.

To read in memorium for Phillip Schofield click here.

ARCH RAYMOND

Born 21 Apr 1921 in Harbin China - 11 Nov 2011

1999 to 2011 Patron of Northside Creative Photography

|

|

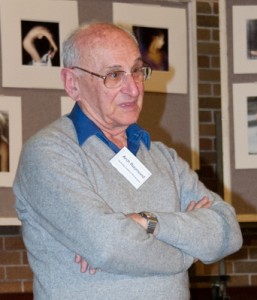

| Arch Raymond | Des Crawley with Arch Raymond |

| Photos courtesy of Chris Barlow | |

Eulogy - Emeritus Professor Des Crawley

Archie Raymond: The Artful Dodger

We are here to celebrate –to reflect on the life of Archie Raymond. Our presence bears testimony to a long life, well lived. He is known to us in various capacities – husband, father, stepfather, grandfather, ex-service man, businessman, mentor, citizen, traveller, benefactor, friend, wine buff, technician, photographer, and artist.

A Renaissance man. An Artful Dodger.

I have been asked to share some thoughts about Archie the photographer. I was asked to make this eulogy humorous, light and entertaining. Hopefully, I meet that brief.

But, I also want make some reflective and respectful comments too. Why? Because Archie, more than anything else, was a respectful and reflective person. He was special. Respect was something he offered and respect was what he gained because of his prodigious talents and personal qualities. He had high personal standards. As I am about to relate he celebrated life and the moment.

No doubt this capacity to celebrate the moment was honed in the formative years of his life linked to convulsive changes in Europe and the onset of WW2 where he served as an airman in one of the most dangerous tasks of that conflict - flying over Europe. It was here that the photography interest of student days was transformed. He related some his difficulties in obtaining film and of getting it processed. He used remnant film from gun cameras for a while and on one occasion used Agfa film only to be told to he could not get it processed as the factory in Germany had been bombed!

This was all good preparation, I would suggest, for dealing with the vagaries of camera club competitions and later the particular challenges of digital photography. I think these early challenges were the key to his success as a photographer. His life experiences between the wars, together with serving his country as an airman made him resilient, resourceful and resolute.

He was rich with personal qualities and skills. He had many stories to tell. He shared these gifts freely.

Unfortunately, he also shared his jokes. Some were really wonderful; others did not travel so well. All were offered fully, freely and accompanied by his ready laughter, mirthful twinkle and mischievous smile. Sometimes I used to think that he actually gained more fun out of watching the impact of his joke than the joke itself. Many of them were really offered with more enthusiasm than judgment. But, his jokes endeared him to me because in sharing his humour he was really saying that he valued who I was and that he cared for and about me. It was an endearing quality. He did this with many people privileged to share his space.

I knew he cared.

The Archie I knew had already packed so much into his life when I first met him in 1987.

By then he had already had a full life with its fair share of drama, poetry, tragedy, of disappointment, of triumph, of sacrifice, of family lost in the convulsive world of Europe, of a new family created in Australia and of personal disaster. He had had enough travail to swamp if not swallow lesser individuals. Archie surmounted all. His life story by the time I first met him was like so many we have come to know and encapsulated in that redolent phrase – the migrant experience.

Archie had survived the war, he had survived the transition to a new world and the stress and strain of establishing a business and a new life, of dealing with illness, of loss as well as the discovery that another life could be built, of new happiness and opportunity and scope to chart yet another pathway into his retirement years. I dwell on these matters simply to make the point that it was these life experiences that made him the great photographer that he was. He did not dwell on the past nor did he see the world as owing him anything. He was entrepreneurial – a risk taker.

We first met on a photographic safari that traveled in an eccentric fashion from Sydney to Darwin and back –an eight week test of personal, physical and photographic qualities. Some of us passed this test, some didn’t. Some of those travellers are here today. Our eight weeks were long enough to forge friendships that have lasted despite what we tried to do to each other on that trip. For some reason Archie and I hit it off and spent many wonderful moments together and we shared much. Instant mateship. Instant friendship.

His was a distinctive presence on this trip. Frankly, he was the only one that had any class. Most of us had Nikons or Canons and that it was it. Archie had a Nikon and a Mary. He, she had class. This was a formidable combination that left all of us down the back of the bus in awe. You see the rest of us were daggy. Arch and Mary were up front of the bus and way out in front in most every other way too. At one stage we even canvassed the idea that we would put up their tent for them. However, we were not that daggy. Later, after the trip, some of us formed a photographic club/group called the DAGS. We called it the Digital Artists Group but really, it has another meaning altogether. It survives.

Archie and I spent a good deal of time together on this trip. We bounced ideas, we related experiences, and we tested our shared insights in all manner of things. There is something about a bush toilet that brings out the best in friendships. Moreover, twenty people cannot camp at Bull’s Hole Creek in the middle of Australia under a canvas canopy and hide too much. We shared 24 hours a day for nearly eight weeks. There is a lifetime of stories in what we did or failed to do. I plan to share a couple and it is true there might be a tad of exaggeration only because I know Archie would expects that of me.

One sharing moment we had I have always remembered. It occurred when he and I were left behind standing together under a rock outcrop in Kakadu National Park. It was a place called Nourlangie. We were looking at a wonderful, complex Aboriginal cave and wall painting display. We were looking at the marks - ancient marks - made by Aboriginal Australians that told stories of their world, their Dreaming, their history and love of country. Archie was moved by these marks, by this artistry, these poignant echoes of the past. We reflected on our own mortality and what marks we might leave. This discussion was sharpened by the presence of some graffiti made by recent visitors to this site. Graffiti that revealed the unctuous, witless, febrile, vacuous marks of more recent visitors. Archie used a number of expletives to describe how he felt about this. In the interest of propriety I have used – unctuous, witless, febrile and vacuous to describe what Archie said. Archie was forthright in rejection of this behavior. He was clear and to the point. He despaired at the insensitivity this graffiti betrayed.

He could be terse, torrid and tough. He made his views of this cultural imperialism –this vandalism - very clear. Up to that moment I had only liked him. After that I admired him. He did not like the modern marks and said as much. We had more in common than I had imagined!

Archie was a photographer and so he was interested in marks. Photographers make marks. We leave marks when we create a photograph - we leave something of ourselves on the print. Archie was a superb photographer. He made wonderful marks. He has left an enormous photographic legacy to complement and extend the legacy he has left in the other dimensions of his life.

Archie had many gifts as a photographer –

He is known by many as a fine technician. But, this is only half of it. He brought to the darkroom the passion and skills of his interest in chemistry, his interest in photo mechanics and in the creative potential of light sensitive materials. He explored this facet of the medium with the zeal, energy and discipline that he brought to the rest of his life. His interest in, his creative contribution to the alternative processes of photography is legendary. His marks were derived from old world practices now honed and shaped by his expertise, his formidable knowledge and capacity for work. He was a classicist. His work was embedded in the surety of time. He related to the Aboriginal paintings simply because like them he had a strong sense of time, of nostalgia of yester-year and what time past tells us about time present and time future. His photography was time-based, bringing to life his memories, experiences and perception, his imagined world using techniques and technologies that were part of the formative years of photography. He demonstrated that the more things change the more they stayed the same. He bridged the old world and the new in terms of his life as well as in his making of marks.

It was dangerous to go to his home. You knew that within a few minutes you would be in his cave. His darkroom filled with labels, smells, experiments, an overflowing rubbish bin and a festoon of immaculate prints suspended from line. Next he would be showing you his work. That meant only the last 200-300 prints. Each seemed better than the other and he handled them with gentleness and an affection that only someone who knows of the importance of making marks can do. It was a special moment because in every sense of the meaning one was being privileged to view what is now his legacy. His marks on a wall.

What was really good about this viewing experience was the lunch that followed and the cracker jack conversation, which inevitably turned to Mary and her work. Her enamel art and one knew that shortly we would go to the other cave and see the creative output of the other half of the class act. Archie was proud of Mary’s achievements and I had the sense that in in the latter years he spent more time supporting and negotiating his life journey so as to maximize opportunities for Mary to grow not only as a ceramicist but also as a photographer than he did with his own work. He communicated to me great joy and pride in her achievements. He was in awe of her creativity. She in turn encouraged, cajoled and bullied when Archie needed it, to achieve the high goals he had set for himself. Formidable combination.

By any measure Archie was a successful photographer. His work was accepted in salons at national and international level. He was awarded a series of honours too at national and international level in recognition of his creative genius.

These included:

AFIAP -(Artiste FIAP). This is awarded to those authors, whose artistic and technical qualities have been acknowledged through participation in national salons and through the acceptances in a number of international salons under FIAP patronage.

FRPS – Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society – an award that only is given to the best of the best from round the world.

AAPS- Associate, Australian Photographic Society for exhibition success

SSAPS – for services to the state of NSW in photography

The Les Newcombe Prize.

Archie wrote about his art, about the science and the craft of his medium. He exhibited work in one-man shows. He offered workshops to those interested in acquiring his insights into alternative processes.

He was the patron of the SIEP (The Sydney International Exhibition of Photography). This honour reflected his outstanding reputation within the camera club movement but was also in recognition of the extraordinary amount of work that he and Mary did to promote, support and safeguard the operation of the SIEP. This meant they gave up a part of their home and their work places to house and administer this exhibition. Generous, supportive, efficient, effective. It was a team effort. Arch and Mary. He would be really annoyed with me today if I did not say that. Arch and Mary.

He was generous. Every visit I made saw Archie give me something really precious. His time, his ideas. He also would give me books, equipment and consumables for my students. At the time he was dissembling, he was moving on. Making the transition from analogue – where he had been so successful, and moving to the digital realm. He found early on, as we all did, this mode quite frustrating and frequently deferred to Mary. He worked hard on translating his analogue world to digital and was soon developing, making work, utilizing the new technology to create the old world of alternative processes as well as enjoying the liberation that came with the digital. He was fascinated by the potential of the digital imaging world and committed himself to achieving the same level of expressive and imagined seeing for which he was famous.

Archie was also patron of Northside Creative – a superb club known for its unique focus on promoting creativity. They could not have had a better role model than Archie. He was also one of two life members of that club. The other is here today and he now needs to be wrapped in cotton wool as life membership of that organization is special and only special characters – emphasis upon characters – attain that privilege. Indeed, Archie was a character.

I discovered, quite by accident on our photo safari that Archie had an aversion to crocodiles. On this matter he was profoundly sensible as he was committed.

In characteristic fashion he negotiated a classy way of avoiding any real contact with them. Two instances come to mind. First was our late afternoon arrival at Yellow Waters and the selection of our campsite. Tour leadership resolved that we were to camp 10-15 metres from the water’s edge. Our site was a blanket of red dust-cum-sand 15 centimetres thick and covered with tracks and trails that included bird prints, horses hoofs and the tell tale sliding marks of crocodylus porosis – the estuarine croc. Some of us, including Arch demurred that we might camp in such a situation. We were told, by those that should know, we would be safe as there was a crocodile proof fence comprising a single strand of wire hanging limply from a series of decayed posts. That was all that stood between us and the water and clearly was never going to protect us from oblivion if crocodylus porosis was going to visit us. Archie was brilliant in this situation. He offered us the leadership that only a class act could promote. He advised all concerned that he was suffering from a bad back and needed to sleep in a proper bed for a day or so and quickly negotiated a place for he and Mary at the nearby luxury hotel. Brilliant.

The rest of us camped. Woody and I worked on the basis that if we were far enough away from the water and ensured that a tent or two of tasty other photographers were between us and the water we would be safer. This we did only to be awakened during the night by the primeval sounds of a wild horse in its death throes as a crocodile took it some 100 metres or so from where we were camping. The only thing that stopped us all joining Arch and Mary in their room at the hotel was the thought that stepping outside the tent was inviting trouble….with teeth.

We survived, this is self-evident. Some of us are here this morning and will agree that I have exaggerated a tad. Just a tad. I feel comfortable doing so as Archie was a tad larger than life himself!! In any event……..

Archie and Mary arrived from the safe haven of their luxury hotel and rejoined ‘sorry city’ as I called it, our camp site – our collection of derelict tents - the next morning. This was the beginning of the second instance where Archie’s aversion to crocs was to manifest itself. Archie and Mary joined us for our well, infamous boat trip on Yellow Waters. Some cynics amongst us had noted that morning that Arch was now moving quite freely and his back did not seem at this point to be a problem. After all, with the prospect of fabulous photography in the offing why would a sore back hinder his movements? This all soon changed. In fact, the moment we saw the boat unhooked from the trailer where it had been stored on the journey from Darwin matters started to become serious. The boat suddenly now looked quite small and indeed fragile. We were expected to get into this vessel and sail forth on Yellow Waters. To join the jacana, ibis, jabiru, sea - eagles and crocs.

It was a metal flat - bottomed boat best described as a ‘tinny’. It was designed for about four people and we put six into it. It seemed OK. Empty, it had 20 cm of freeboard. With six occupants the tinny settled into the water leaving about 10 cm between the crocs and us. Now as we set forth we discovered that the outboard motor seemed to have a mind of its own. It would surge and shudder in random order and obviously was well beyond the control of our tour leader. Silence prevailed. We surged and shuddered towards a distant mangrove complex where we were assured we would find crocs, birds and other nature stuff….none of us thought we would make it. Clearly, Archie did not.

Some five metres or so into our journey Archie noticed we had water in the bottom of the boat and was told – by the outboard motor engineer – cum - driver (the same chap that gave us advice about the croc proof fence) this water was quite OK. The boat was designed to have water slopping about in it. In any case this water was at the back of the boat and would not worry any of the folk such as Arch who as we expected, as we were used to, sat up the front. Archie kept making sidelong glances at the back of the boat and offered me beseeching looks. I did not think it was a good time to tell him I could not swim but thought his camera bag had great flotation capability. Moments later the water in the tinny had increased in volume and in depth and was now clearly beginning to move with each surge of the engine to form a mini wave action to and fro – slopping from the front to the back of boat creating some serious stability issues. This was alarming to most of us and to Arch the cause for apoplexy. His camera bag was getting wet.

An examination of the cause for this water was sought by Arch who gently but firmly reminded us that the four metre crocodile on the bank some 10 metres away seemed quite interested in us. Indeed, we observed it had just slipped off the mud and we all watched in silence its trail of bubbles on the surface that came directly towards us, the bubbles, and the croc attached to them, went under the boat and continued into the centre of the lake. In this instance Archie discovers that the bung – the plug intended to be used to empty the boat during the cleaning of its interior - had slipped out and was floating idly about in the boat. He informed us, with just the slightest note of panic that we were in fact sinking…. sinking. Suffice to say that no self-respecting crocodile would come near us given what Archie said about that boat at that particular moment. Moreover, he made it clear he did not survive flying over Germany to sink in a bathtub floating on Yellow Waters.

We did continue our journey after re-instating the bung confident that the captain of the ship would continue to use Archie’s hat to bail vigorously. The captain was a much better bailer than he was advisor about all things navigable. We obtained great shots of jabiru, crocs, Jesus birds and water lilies. The day was a success despite us and thanks to Archie. For years later each time I mentioned crocodiles Archie would go pale and start to change the subject. So, I will not mention, on another photo adventure - hot air ballooning - and the balloon that refused to fly other than to say Archie had as much luck with balloons as he had with tinnies. He said as much as we sat entangled in a barbed wire fence with the hot air balloon tipping over attempting to embrace the wheat field we had bounced in and along for 300 metres or so. We walked a long way that morning.

Archie was a traveller. He and Mary made many photo journeys in the last 25 years or so. I checked. None involved crocodiles or balloons. Indeed, I would suggest that journeys made to the Antarctic. South America, Siberia, the Danube were all noteworthy for locales free of crocs. But, they did have great experiences and achieved fabulous photographic outcomes made all the better when Archie would share them over a glass of wine and a great meal. They were wonderful moments. You see for Archie photography was as much about friendship and fellowship as it was the chase for imagery.

One of the last occasions Arch and I met he gave me full and unfettered access to his photographic world. He essentially told me to take anything that I liked. Take it and give it to your students, he said. Enlargers, cameras, lenses, chemistry and literature – he gave them all. All this treasure is now distributed to a large community of young graduates. They never met the man who helped them get a start with their studies or with their profession. I tried to tell them. But, there are really no words adequate to sum up the life of a man who lived and enriched all with whom he came into contact. In the end I just told them all that they were given to me by a friend. That was enough.

The Navajo –and many other cultures borne of antiquity measure time in unique ways – many have an expression about death that varies in emphasis but contains, in essence the sentiment that says, “all good people die empty”. That is, these ancient cultures believe, that each individual has a rich range of qualities, experiences, skills and stories to tell. That people make marks. They have enough marks for one lifetime and when they have shared them all, when they are empty, when they have said all that needs to be said, when they have made all of their marks - it is time to die. It took Archie 90 years to die. By Navajo standards, by any standards, he must have been truly a great person.

Archie had so much to offer it took Archie a long time to empty! All that wisdom, that experience just poured out in a wave of care and concern for his fellow human beings. His creative genius seemed endless, his passion for image making undiminished until near the end.

I am not sure that he would have thought too much about the inevitability of his illness. He always seemed so full of the next project.

Knowing of his exploration and experimentation with digital technology and given our many great moments together he would appreciate this final point. In preparing this eulogy my attention was drawn to a web site that advertised in the following:

“25 written eulogies for $20. That is less than a dollar a eulogy” it beckoned. It pleaded.

Arch would just love that. He would see the dark humour in that and smile. There was the beginning of an Archie joke in that promotion.

I will remember that smile. It came across his face each time we shared images together. That smile epitomized him as the Artful Dodger!

Each of us will remember him in our own way. But, remember him we will. He made his mark – a photographer extraordinaire.

Des Crawley,

Emeritus Professor

Tribute - Jacques Roussel

Northside Creative Photography has lost a great friend and mentor when Arch passed away last week at the age of 90.He invented many darkroom techniques that he willingly taught to club members in tutorials that he gave in his house. Some of these he explained in his beautifully illustrated book: “The Artful Dodger”.

Arch strongly promoted the idea of “Free Style” and creativity. With his wife Mary he devised the club’s first definition of creative photography. I still remember the stunning 3D model scene he entered in our first National Freestyle competition.

In one of the few presentations I made to the club I almost completely lost my voice and coughed non stop. Arch came to the rescue with his supply of cough lollies.

On the 21st of August 2002 Arch presented a “Retrospective Exhibition and Talk”. St David’s Hall was packed to capacity and the attendance was a who’s who of the photographic world - amateur and professional. We were enthralled by the superb quality of his prints and the variety of his subjects.

Arch was a great storyteller and had an encyclopaedic memory for jokes.

When he reached an age where we find it difficult to approach new ways of doing things, he embraced the digital technology and mastered it in no time, producing magnificent prints.

Arch with his wife Mary travelled the world from one Pole to the other adding constantly to their enormous collection of stunning images.

Arch became “Patron” of Northside Creative Photography in 1999 and Life member in 2007.

Arch entered many competitions and collected many well deserved awards. Arch gained his Associateship of the Royal Photographic Society (UK) in 1988, the Fellowship of the Royal Photographic Society in 1990. In 1991 he gained the award of Artiste de la Federation Internationale de l’Art Photographique (Belgium).

Arch exhibited his work in Sydney, Melbourne and London and he has won numerous gold and silver awards in national and International Photographic Exhibitions.

He also wrote numerous articles for the Australian and British press.

Arch was very concerned that our club functioned to the highest possible professional level and his advice were always listened to with great attention.

Arch will be very much missed for his friendship, his knowledge, his sharing and his great sense of humour.

Jacques Roussel Some of Archie's work can be seen here.MARY RAYMOND

Mary Raymond passed away peacefully on the night of Sunday 15th January, after a long battle with illness.

Mary Raymond was born in Randwick in Sydney’s eastern suburbs in 1939 and has worked intensively with enamels for over 40 years. Her parents were recently arrived refugees from the frightening holocaust that Europe had become during the 1930’s. Her parents, George and Ilse, came from very wealthy families. Nearly all that wealth was left behind. George was able to bring enough money to buy a large sandstone house in Randwick where Mary spent her childhood years.

Selected for Sydney Girls High she was a good student, a little mischievous if the stories of a couple of school friends are to be believed. From there Mary went on to Sydney University to study Pharmacy.

She studied at The School of Colour and Design and learned a variety of enamel techniques at workshops in Australia and overseas. An associate of the Royal Photographic Society, Mary is also a keen photographer and has traveled widely in outback Australia.

Her photographs provide the inspiration for her designs. Her enamels have been shown in exhibitions in Australia, Germany and America. One of her largest commissions is a work “The Escarpment” for the foyer of the St George Private Hospital in Kogarah, NSW. This work is a mural 1.5 x 6 metres.

Enamel is glass fused to metal at room temperatures ranging from 750-950 degrees C. multiple firings are required to build up color and design layer by layer. The firings are short and hot, each piece being fired individually and requiring at least eight firings. Since the surface is actually glass, enamel is very durable, non-fading and washable.

Mary’s plates and bowls, both regular and reticulated shapes, are sought after by collectors and feature in many private and public collections.